lift is developed. This feature provides the pilot with

complete control of the lift developed by the rotor

blades.

ROTOR AREA

One assumption made is that the lift depends

upon the entire area of the rotor disc. The rotor disc

area is the area of the circle, the radius of which is

equal to the length of the rotor blade. Engineers

determined that the lift of a rotor is in proportion to

the square of the length of the rotor blades. The

desirability

of large rotor disc areas is readily

apparent. However, the greater the rotor disc area, the

greater the drag, which results in the need for greater

power requirements.

.-. /

PITCH OF ROTOR BLADES

If the rotor is operated at zero pitch (flat pitch), no

lift will develop. When the pitch increases, the lifting

force increases until the angle of attack reaches the

stalling angle. To even out the lift distribution along

the length of the rotor blade, it is common practice to

twist the blade. With the twist, a smaller angle of

attack results at the tip than at the hub.

SMOOTHNESS OF ROTOR BLADES

Tests have shown that the lift of a helicopter

increases by polishing the rotor blades to a mirrorlike

surface. By making the rotor blades as smooth as

possible, the parasite drag reduces. Dirt, grease, or

abrasions on the rotor blades cause increased drag,

which decreases the lifting power of the helicopter.

DENSITY ALTITUDE

In formulas for lift and drag, the density of the air

is an important factor. The mass or density of the air

reacting in a downward direction causes the lift that

supports the helicopter.

‘Density is dependent on two factors. One factor

is altitude, since density varies from a maximum at

sea level to a minimum at high altitude. The other

factor is atmospheric

changes.

Because of the

atmospheric changes in temperature, pressure, or

humidity, density of the air may be different, even at

the same altitude.

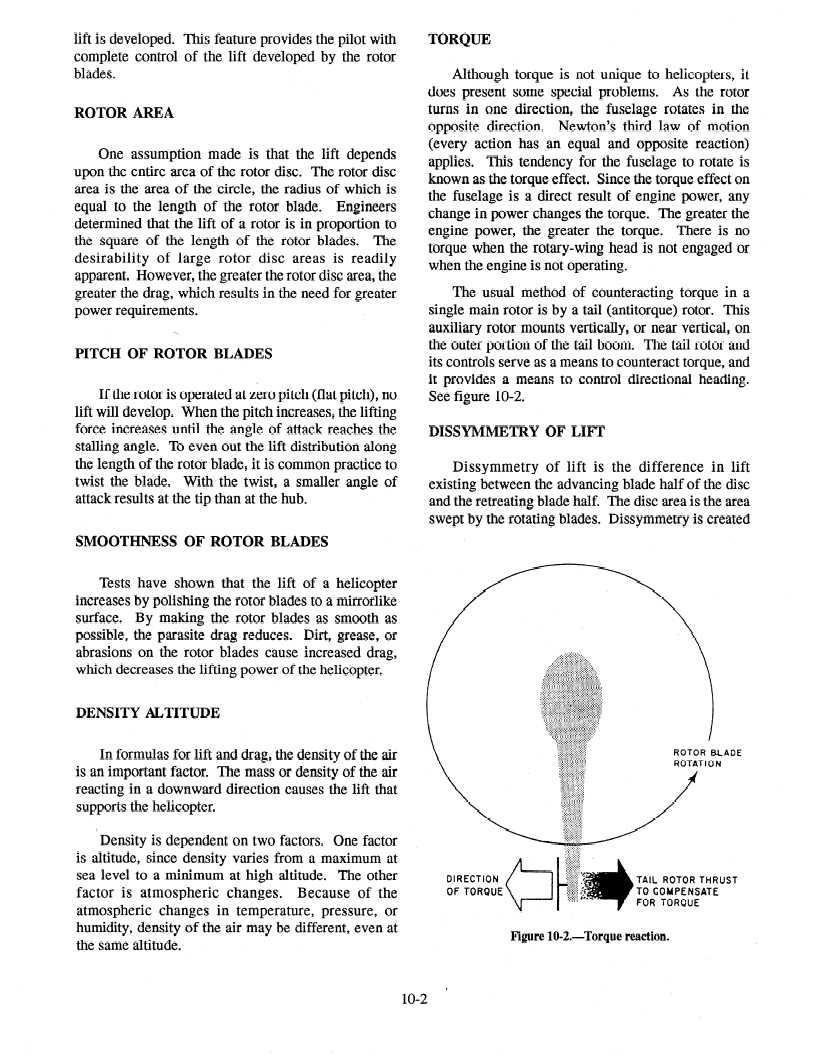

TORQUE

Although torque is not unique to helicopters, it

does present some special problems.

As the rotor

turns in one direction, the fuselage rotates in the

opposite direction.

Newton’s third law of motion

(every action has an equal and opposite reaction)

applies. This tendency for the fuselage to rotate is

known as the torque effect. Since the torque effect on

the fuselage is a direct result of engine power, any

change in power changes the torque. The greater the

engine power, the greater the torque.

There is no

torque when the rotary-wing head is not engaged or

when the engine is not operating.

The usual method of counteracting torque in a

single main rotor is by a tail (antitorque) rotor. This

auxiliary rotor mounts vertically, or near vertical, on

the outer portion of the tail boom. The tail rotor and

its controls serve as a means to counteract torque, and

it provides a means to control directional heading.

See figure 10-2.

DISSYMMETRY

OF LIFT

Dissymmetry

of lift is the difference in lift

existing between the advancing blade half of the disc

and the retreating blade half. The disc area is the area

swept by the rotating blades. Dissymmetry is created

. . . . . .

*.**..*:..,

*.*,......*,

.

*.*.*.*.*.*.

..*...m.*.*.

..:.:.:.:.:.

*.-**.'.*,-

S.'....

..,.

DiRECTiON

:.‘A’.‘.’

.

v.*.*.*.

.‘.‘.‘.‘.

OF TORQUE

ot

.

.

...‘.

:.>:.:.

TAIL ROTOR THRUST

-.*.*2..

‘A*,‘,

‘.‘A*,~

‘........

TO COMPENSATE

.:.:.:.:

FOR TORQUE

Figure lo-2.-Torque

reaction.

10-2