HAMMERS

A toolkit for nearly every rating in the Navy would

not be complete without at least one hammer. In most

cases, two or three are included, since they are

designated according to weight (without the handle)

and style or shape. The shape will vary according to the

intended work.

Machinists' Hammers

Machinists' hammers are mostly used by people

who work with metal or around machinery. These

hammers are distinguished from carpenter hammers by

a variable-shaped peen, rather than a claw, at the

opposite end of the face (fig. 1-48). The ball-peen

hammer is probably most familiar to you.

The ball-peen hammer, as its name implies, has a

ball that is smaller in diameter than the face. It is

therefore useful for striking areas that are too small for

the face to enter.

Ball-peen hammers are made in different weights,

usually 4, 6, 8, and 12 ounces and 1, 1 1/2, and 2

pounds. For most work a 1 1/2 pound and a 12-ounce

hammer will suffice. However, a 4- or 6-inch hammer

will often be used for light work such as tapping a

punch to cut gaskets out of sheet gasket material.

Machinists' hammers may be further divided into

hard-face and soft-face classifications. The hard-faced

hammer is made of forged tool steel, while the

soft-faced hammers have a head made of brass, lead, or

a tightly rolled strip of rawhide. Plastic-faced hammers

or solid plastic hammers with a lead core for added

weight are becoming increasingly popular.

Soft-faced hammers (fig. 1-48) should be used

when there is danger of damaging the surface of the

work, as when pounding on a machined surface. Most

soft-faced hammers have heads that can be replaced as

the need arises. Lead-faced hammers, for instance,

quickly become battered and must be replaced, but have

the advantage of striking a solid, heavy nonrebounding

blow that is useful for such jobs as driving shafts into or

out of tight holes. If a soft-faced hammer is not

available, the surface to be hammered may be protected

by covering it with a piece of soft brass, copper, or hard

wood.

Using Hammers

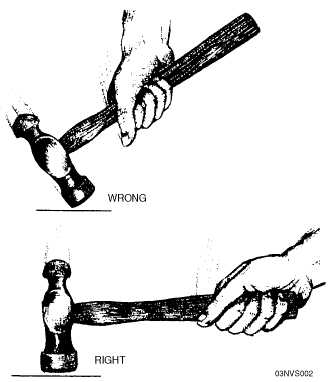

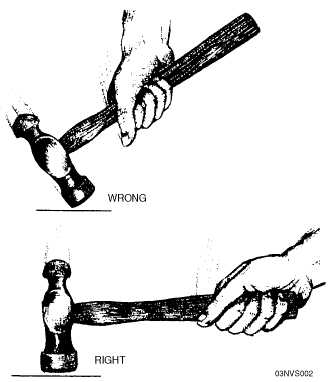

Simple as the hammer is, there is a right and a

wrong way of using it. (See fig. 1-49.) The most

common fault is holding the handle too close to the

head. This is known as choking the hammer, and

reduces the force of the blow. It also makes it harder to

hold the head in an upright position. Except for light

blows, hold the handle close to the end to increase

leverage and produce a more effective blow. Hold the

handle with the fingers underneath and the thumb along

side or on top of the handle. The thumb should rest on

the handle and never overlap the fingers. Try to hit the

object with the full force of the hammer. Hold the

hammer at such an angle that the face of the hammer

and the surface of the object being hit will be parallel.

This distributes the force of the blow over the full face

and prevents damage to both the surface being struck

and the face of the hammer.

MALLETS AND SLEDGES

The mallet is a short-handled tool used to drive

wooden-handled chisels, gouges, and wooden pins, or

to form or shape sheet metal where hard-faced

hammers would mar or damage the finished work.

Mallet heads are made from a soft material, usually

wood, rawhide, or rubber. For example, a rubber-faced

mallet is used for knocking out dents in an automobile.

It is cylindrically shaped with two flat driving faces that

are reinforced with iron bands. (See fig. 1-48.) Never

use a mallet to drive nails, screws, or any other object

that can damage the face of the mallet.

1-31

Figure 1-49.—Striking a surface.