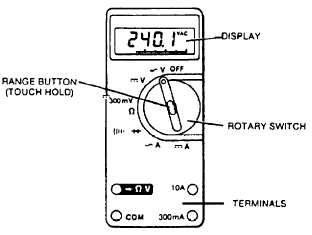

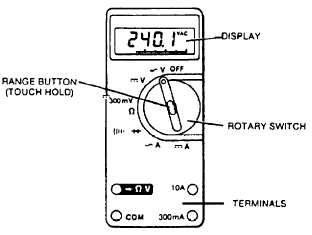

Figure 3-11.—A typical electronic multimeter.

precautions and requirements for quality assurance

verification.

Personnel involved in troubleshooting and per-

forming operational checks should consult the records

maintained in maintenance control and/or the work

center register. Reference to records of previous

maintenance may show a progressive deterioration of a

particular system or a previous discrepancy. This

procedure could be helpful in pinpointing the cause of

the malfunction currently being experienced.

ELECTRICAL FAILURES

Since practically all systems now have some

electrically controlled components, troubleshooting

must also include the related electrical circuits in many

instances. Although an AE is generally called upon to

locate and correct electrical troubles, you should be able

to check circuits for loose connections and even perform

continuity checks when necessary. Therefore, a

knowledge of electrical symbols and the ability to read

circuit diagrams is necessary. Figure 3-4 illustrates the

electrical symbols commonly found in schematic

diagrams.

Loose connections are located by checking all

connectors in the circuit. A connector that can be turned

by hand is loose and should be tightened hand tight.

A continuity check is simply a matter of

determining whether or not the circuit to the selector

valve, or other electrically controlled unit, is complete.

Continuity checks are made with the use of a multimeter.

The name multimeter comes from MULTIPLE

METER, and that is exactly what a multimeter is. It is a

dc ammeter, an ac ammeter, a dc voltmeter, an ac

voltmeter, and an ohmmeter, all in one package. Figures

3-10 and 3-11 show the faces of commonly used

multimeters. The applicable instructions should be

consulted prior to equipment operation.

TORQUING OF FASTENERS

Learning Objective: Recognize the importance

of the proper torquing of fasteners and the

required torquing procedures.

Fastener fatigue failure accounts for the majority of

all fastener problems. Fatigue breaks are caused by

insufficient tightening and the lack of proper preload or

clamping force. This results in movement between the

parts of the assembly and bending back and forth or

cyclic stressing of the fastener. Eventually, cracks will

progress to the point where the fastener can no longer

support its designed load. At this point the fastener fails

with varying consequences.

TORQUING PROCEDURES

For the nut to properly load the bolt and prevent

premature failure, a designated amount of torque must

be applied. Proper torque reduces the possibility of the

fastener loosening while in service. The correct torque

to apply when you are tightening an assembly is based

on many variables. The fastener is subjected to two

stresses when it is tightened. These stresses are torsion

and tension. Tension is the desired stress, while torsion

is the undesirable stress caused by friction. A large

percentage of applied torque is used to overcome this

friction, so that only tension remains after tightening.

Proper tension reduces the possibility of fluid leaks.

3-19